Crashing Bottles

State’s first wine industry and its demise a century ago

By Peter Holmstrom

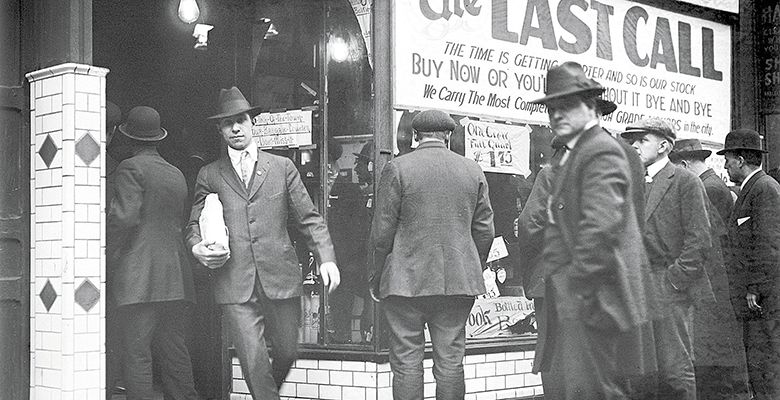

“One thousand gallons of grape wine dumped into the Columbia River here Wednesday.” So read the morning issue of The Oregonian Oct. 25, 1919; describing the previous night’s raids by local law enforcement in the town of St. Helens.

Read today, this would come as a shock. We might laugh, or worry about the safety of the truck driver who must have been involved in an accident. For readers of the 1919 article, the situation was nothing new. Prohibition had arrived.

“Sales, historical records, information; Prohibition is really where it all stops,” according to the author of Wines of Walla Walla Valley, Catie McIntyre Walker.

It may be hard to imagine today, but the wine industry in the Pacific Northwest was firmly on its way to becoming the world renowned wine-growing region it is known as today. Vineyards and wineries filled the state, much as they do now. Emigrants from Europe carried with them the tastes and preferences of their homeland, making regions of Oregon and Washington distinctive for growing specific varietals. Grape production began with the first settlers to the region, predating Oregon statehood.

The first vines were grown in the Willamette Valley in 1847 by Henderson Luelling, who allegedly won a gold medal for his wine at the 1859 California State Fair. German immigrants Edward and John Von Pessels, as well as Adam Doerner, were known to have brought Zinfandel, Riesling and Sauvignon (no record of whether Cabernet or Blanc) to the Umpqua Valley in Southern Oregon.

While farther north in the Willamette Valley, Ernst Reuter was known to be growing Pinot Blanc, Chardonnay, and numerous others on David’s Hill, west of Forest Grove. Italian varietals were becoming popular in the Walla Walla region because of its large Italian population — vines of the rare Cinsault grape still grow there. By 1860, Oregon was producing about 2,600 gallons of grape juice, though it’s unknown how much was wine. This number increased exponentially over the next few years. Jackson County alone was making more than 15,000 gallons of wine two decades later.

The industry was quite a bit different at the time. Rather than large wineries, winegrowers during pre-Prohibition were small, family operations, putting their wine into kegs and barrels to sell at local taverns and wine shops.

“Italian farmers, before the days of liquor laws, were making their wines and needing to support their families. [They] would bring their wines into the local taverns or wine shops and sell them for money or barter for supplies. These were there tasting rooms!” says McIntyre Walker.

Not only was the public benefiting from the wine industry, the state was also prospering as well. Tax revenues from alcohol sales accounted for 25 percent of the city of Portland’s budget in the days prior to Prohibition. Similar profits were experienced throughout the Northwest. Wineries, breweries and liquor stores were regional “mom and pop” establishments taxed by the city, affecting a sizable contribution to the local economy.

But this ideal world crashed down in 1914.

Voters in Oregon and Washington would have felt little surprise to see a ballot measure to prohibit the sale and manufacture of alcohol in 1914. In fact, they would have expected it. Prohibition had first been proposed in Oregon as early as 1844, 15 years before Oregon became a state.

Western expansion and the economic boom that followed resulted in a huge increase in population within a very short period of time. Oregon’s population went from 12,093 to 52,465 in the years between 1850 and 1860; and would continue to nearly double ever decade through 1900.

Along with the benefits from this spike in population, there were negatives. The timber, shipping, and mining communities that made up many of the Pacific Northwest cities had a highly transient population — estimated at 50 percent in Portland during 1866. These people would come into town after a long season of working in the mountains or mines, looking to blow their paycheck anyway they could. What followed was a dramatic increase in levels of prostitution, gambling, drug use and alcoholism. The saloons were the common sites for these illicit activities.

“The stench of stale beer and whisky often mix with the nauseating smell of vomit,” recalled a schoolteacher on her arrival in Portland in 1902.

By the turn of the century, public opinion began to shift. The increase in population also included families with children. Many, who saw the “sin and wickedness” infesting their city, realized a solution: Get rid of the alcohol, and the sin will go away.

“Walla Walla was absolutely filled with liquor stores that promoted wine, as well as many taverns and pool halls. They said at the time, that there was one alcohol-oriented business per 100 people in Walla Walla. And they were a big, big part of the tax revenue for the city.”

This perspective was not unique to the Pacific Northwest. Cities and states throughout the country were dealing with the same problem. Progressive political movements were springing up in every single metropolis in the country with the hope of drastically altering the fabric of the nation’s existence.

National organizations such as the Women’s Temperance League, and the Anti-Saloon League canvassed the countryside, delivering speeches in churches, town halls and public streets.

By 1914, the prohibition of alcohol was on the ballot, but the supporters of Prohibition had one large advantage: Women had won the right to vote. This was their first election as part of the voting pool.

Oregon’s Measure 17, and Washington’s Measure 3, went before the voters Nov. 3, 1914. With one of the highest percentage of voter turnout in Oregon’s history, both Northwest states approved the prohibition of alcohol, four years before national Prohibition was passed with the Volstead Act.

Winemakers, breweries and saloons were given a 14-month grace period before they had to shut their doors on Jan. 1, 1916. Many winemakers thought this was the end; but there were some that resisted.

Freshly out of a job, winemakers turned their attention to making “non-alcoholic” fruit wine, or wines specifically made for religious purposes. Not surprisingly, the number of pastors and rabbis rose drastically during these years. However, these alternatives were not enough for most small family wineries, and production was streamlined into larger conglomerates — Napa’s Beringer Wines, for example.

While family winemakers suffered, the vineyards were actually successful. Bootlegging was wildly successful during Prohibition, which contributed greatly to the odd increase in grape production during those years. The number of vines growing in Oregon jumped from 397,054 in 1919, to 599,943 by 1934. Production of wine moved from barrel rooms to basements and bathtubs.

However, with the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, winemaking in Oregon and Washington did not improve. Labor shortages, mechanization of farming equipment, post-WWII economics and competition from California lead the industry to dwindle and be largely forgotten. Farmers became orchardists; barrel rooms, storehouses; and wine shops, department stores. The potential and success of the early wine industry was known only to the select few who remembered those days.

Luckily for us, enterprising winemakers started experimenting with Oregon and Washington again beginning in the 1960s, and by the late 1990s, wine growing regions were once again garnering worldwide appreciation. But it does make one wonder: How different would the wine industry be today, if Prohibition never existed?

Peter Holmstrom is a freelance wine and beer writer who thoroughly enjoys researching his articles. Having grown up in the heart of the Columbia River Gorge, surrounded by vineyards and breweries, it is no surprise he has decided to make the study of these art forms his priority. His work has been featured in Portland Monthly Magazine, the Oregon Beer Growler and Sip Northwest.

Peter Holmstrom is a freelance wine and beer writer who thoroughly enjoys researching his articles. Having grown up in the heart of the Columbia River Gorge, surrounded by vineyards and breweries, it is no surprise he has decided to make the study of these art forms his priority. His work has been featured in Portland Monthly Magazine, the Oregon Beer Growler and Sip Northwest.